Prescience and Precedent

In the previous articles (part 1 and part 2), we discussed both the modeling and rating of CDOs and their tranches. In this article, we will discuss the rating of synthetic CDOs and those fabled “super senior” tranches. As mentioned in the previous articles, I highly recommend that you read my article on Synthetic CDOs and my article on tranches.

Funded And Unfunded Synthetic CDOs

As explained here, the asset underlying a synthetic CDO is a portfolio of the long positions of credit default swaps. That is, investors in synthetic CDOs have basically sold protection on various entities to the CDS market through the synthetic CDO structure. Although most CDS agreements will require collateral to be posted based on who is in the money (and may also require an upfront payment), as a matter of market practice, the protection seller does not fund the long position. That is, if A sold $1 million worth of protection to B, A would not post the $1 million to B or a custodian. (Note that this is a market convention and could change organically or by fiat at any moment given the current market context). Thus, B is exposed to the risk that A will not payout upon a default.

Because the long position of a CDS is usually unfunded, Synthetic CDOs can be funded, unfunded, or partially funded. If the investors post the full notional amount of protection sold by the SPV, then the transaction is called a fully funded synthetic CDO. For example, if the SPV sold $100 million worth of protection to the swap market, the investors could put up $100 million in cash at the outset of the synthetic CDO transaction. In this case, the investors would receive some basis rate, usually LIBOR, plus a spread. Because the market practice does not require a CDS to be funded, the investors could hang on to their cash and simply promise to payout in the event that a default occurs in one of the CDSs entered into by the SPV. This is called an unfunded synthetic CDO. In this case, the investors would receive only the spread over the basis rate. If the investors put up some amount less than the full notional amount of protection sold by the SPV, then the transaction is called a partially funded synthetic CDO. Note that the investors’ exposure to default risk does not change whether the transaction is funded or unfunded. Rather, the SPV’s counterparties are exposed to counterparty risk in the case of an unfunded transaction. That is, the investors could fail to payout upon a default and therefore the SPV would not have the money to payout on the protection it sold to the swap market. Again, this is not a risk borne by the investors, but by the SPV’s counterparties.

Analyzing The Risks Of Synthetic CDOs

As mentioned above, whether a synthetic CDO is funded, unfunded or partially funded does not affect the default risks that investors are exposed to. That said, investors in synthetic CDOs are exposed to counterparty risk. That is, if a counterparty fails to make a swap fee payment to the SPV, the investors will lose money. Thus, a synthetic CDO exposes investors to an added layer of risk that is not present in an ordinary CDO transaction. So, in addition to being exposed to the risk that a default will occur in any of the underlying CDSs, synthetic CDO investors are exposed to the risk that one of the SPV’s counterparties will fail to pay. Additionally, there could be correlation between these two risks. For example, the counterparty to one CDS could be a reference entity in another CDS. Although such obvious examples of correlation may not exist in a given synthetic CDO, counterparty risk and default risk could interact in much more subtle and complex ways. Full examination of this topic is beyond the scope of this article.

In a synthetic CDO, the investors are the protection sellers and the SPV’s counterparties are the protection buyers. As such, the payments owed by the SPV’s counterparties could be much smaller than the total notional amount of protection sold by the SPV. Additionally, any perceived counterparty risk could be mitigated through the use of collateral. That is, those counterparties that have or are downgraded to low credit ratings could be required to post collateral. As a result, we might choose to ignore counterparty risk altogether as a practical matter and focus only on default risk. This would allow us to more easily compare synthetic and ordinary CDOs and would allow us to use essentially the same model to rate both. Full examination of this topic is also beyond the scope of this article. For more on this topic and and others, go here.

Synthetic CDO Ratings And Super Senior Tranches

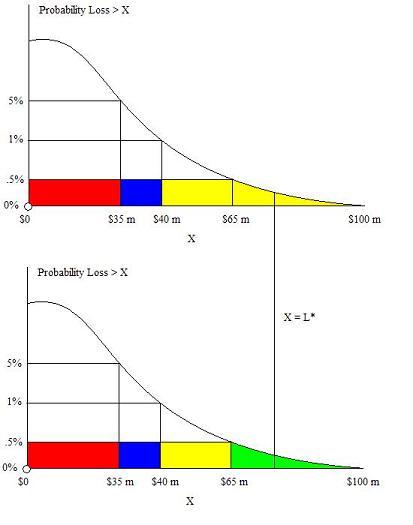

After we have decided upon a model and run some simulations, we will produce a chart that provides the probability that losses will exceed X. We will now compare two synthetic CDOs with identical underlying assets but different tranches. Assume that the tranches are broken down by color in the charts below. Additionally, assume that in our rating system (Joe’s Rating System), a tranche is AAA rated if the probability of full repayment of principle and interest is at least 99%.

Note that our first synthetic CDO has only 3 tranches, whereas the second has 4, since in in the second chart, we have subdivided the 99th percentile. The probability that losses will reach into the green tranche is lower than the probability that losses will reach into the yellow tranches of either chart. Because the yellow tranches are AAA rated in both charts, certain market participants refer to the green tranche as super senior. That is, the green tranche is senior to a AAA rated tranche. This is a bit of a misnomer. Credit ratings and seniority levels are distinct concepts and the term “super senior” conflates the two. A bond can be senior to all others yet have a low credit rating. For example, the most senior obligations of ABC corporation, which has been in financial turmoil since incorporation, could be junk-rated. And a bond can be subordinate to all others but still have a high credit rating. So, we must treat each concept independently. That said, there is a connection between the two concepts. At some point, subordination will erode credit quality. That is, if we took the same set of cash flows and kept subdividing and subordinating rights in that set of cash flows, eventually the lower tranches will have a credit rating that is inferior to the higher tranches. It seems that the two concepts have been commingled in the mental real estate of certain market participants as a result of this connection.

Blessed Are The Forgetful

So is there a difference between AAA notes subordinated to some “super senior” tranche and plain old senior AAA rated notes? Yes, there is, but that shouldn’t surprise you if you distinguish between credit ratings and seniority. You should notice that the former note is subordinated while the latter isn’t. And bells should go off in your mind once you notice this. The rating “AAA” describes the probability of full payment of interest and principle. Under Joe’s Ratings, it tells you that the probability that losses will reach the AAA tranche is less than 1%. The AAA rating makes no other statements about the notes. If losses reach the point X = L*, investors in the subordinated AAA notes (the second chart, yellow tranche) will receive nothing while investors in the senior AAA notes (the first chart, yellow tranche) will not be fully paid, but will receive a share of the remaining cash flows. This difference in behavior is due to a difference in seniority, not credit rating. If we treat these concepts as distinct, we should anticipate such differences in behavior and plan accordingly.

You’ve done a brilliant job. Again. However, didn’t my explanation basically get it right, given the fact that I’m a Grouchofan and you’re an Erdosfan.

“I’m puzzled by the problem. The whole point is to divide up risk, going from least risky to more risky. Clearly, on the ladder of risk, to make this simple, what’s below is riskier than what’s on top. If you’re an investor, that would seem to be the thing you’d really like to know, and it’s simply drawn and simply understood.

In order to create the various levels, a math model was used that allowed you to see bumps or groupings of defaults that you could assign risk to and sell it. The original division has, say, 3 levels, and now you’ve created a fourth. The previous poster’s point is how did this happen. Your model gave you three levels of risk that you could package, so where did the fourth come from? Is it a new model? Has a fourth bump or group been added?

The answer looks like “no”. What’s happened is that within that particular level of risk, one person has agreed to take the losses first. In a sense, that’s what the whole thing looks like. Who takes the hit first. But now that’s all it is, while the original model included default rates. Now, within that grouping of rates, you’ve created a parceling of losses.

In essence, what this Super Senior did was distill the original model down to its basic concept: Who takes the losses first. Within the original risk model which applied to the whole pie, you’ve simply taken one slice, still under the original risk model, and had two people agree that when the risk comes calling, the first person will lose money before the second. It’s a risk within a risk, but , again, when you look at the graph or ladder, it’s pretty obvious where the agreed upon risk stands.”

Next, would you mind explaining Black/Scholes/Merton, the Central Limit Theorem, Gaussian Copulas ( I’m not sure Gauss is thrilled with this ), PRDCs, Currency Trading, and Russell’s Paradox?

No hurry. I’ve got all week.

Thanks again,

Don

Don,

The model didn’t give us any tranches. The model tells us how likely a given level of loss is. Having this information ALLOWS us to dice up the cash flows into tranches at particular ratings levels. Read through the first article again. Hope that clears things up.

Thanks. Don

Like Don I would like to thank you for a good explanation. I do, however, have two questions:

(1) Were super senior tranches ever funded?

and

(2) Were there any super senior tranches that were less than 50% of the notional value of the synthetic CDO (or of the total amount at risk of a hybrid CDO)?

ACC,

There really is no practical way for me to answer either of those questions. You are asking for conclusive answers to market practice questions. I can however give you qualified answers.

As for 1, they are typically unfunded. As for 2, they are typically large tranches, but I’m not going to through out a figure. If you’re truly interested in that level of detail, you should pick up one of the texts by Frank Fabozzi on structured finance.