Systemic Speculation

Pundits from all corners have been chiming in on the debate over derivatives. And much like the discourse that has dominated the rest of human history, reason, temperance, and facts play no role in the debate. Rather, the spectacular, outrage, and irrational blame have been the big winners lately. As a consequence, credit default swaps have been singled out as particularly dangerous to the financial system. Why credit default swaps have been targeted as opposed to other derivatives is not entirely clear to me, although I do have some theories. In this article I debunk many of the common myths about credit default swaps that are circulating in the popular press. For an explanation of how credit default swaps work, see this article.

The CDS Market Is Not The Largest Thing Known To Humanity

The media likes to focus on the size of the market, reporting shocking figures like $45 trillion and $62 trillion. These figures refer to the notional amount of the contracts, and because of netting, these figures do not provide a meaningful picture of the amount of money that will actually change hands. That is, without knowing the structure of the credit default swap market, we cannot determine the economic significance of these figures. As such, these figures should not be compared to real economic indicators such as GDP.

But even if you’re too lazy to think about how netting actually operates, why would you focus on credit default swaps? Even assuming that the media’s shocking double digit trillion dollar amounts have real economic significance, the credit default swap market is not even close in scale to the interest rate swap market, which is an even more shocking $393 trillion market. But alas, we are in the midst of a “credit crisis” and not an “interest rate crisis.” As such, headlines containing the terms “interest rate swap” will not fare as well as those containing “credit default swap” in search engines or newsstands. Perhaps one day interest rate swaps will have their moment in the sun, but for now they are an even larger and equally unregulated market that’s just as boring and uneventful as the credit default swap market.

Credit Default Swaps Do Not Facilitate “Gambling”

One of the most widely stated criticisms of credit default swaps is that they are a form of gambling. Of course, this allegation is made without any attempt to define the term “gambling.” So let’s begin by defining the term “gambling.” In my mind, the purest form of gambling involves the wager of money on the outcome of events that cannot be controlled or predicted by the person making the wager. For example, I could go to a casino and place a $50 bet that if a casino employee spins a roulette wheel and spins a ball onto the wheel, the ball will stop on the number 3. In doing so, I have posted collateral that will be lost if an event (the ball stopping on the number 3) fails to occur, but will receive a multiple of my collateral if that event does indeed occur. I have no ability to affect the outcome of the event and more importantly for our purposes, I have absolutely no way of predicting what the outcome will be. In short, my “investment” is a blind guess as to the outcome of a random event.

Now let’s compare that with someone (B) buying protection on ABC’s bonds through a credit default swap. Assume that B is as villainous as he could be: that is, assume that he doesn’t own the underlying bond. This evildoer is in effect betting upon the failure of ABC. What a nasty thing to do. And why would he do such a thing? Well, B might reasonably believe that ABC is going to fail in the near future based on market conditions and information disclosed by ABC. But why should someone profit from ABC’s failure? Because if B’s belief in ABC’s impending failure is shared by others, their collective selfish desire to profit will push the price of protection on ABC’s bonds up, which will signal to the market-at-large that the CDS market believes that there will be an event of default on ABC issued debt. That is, a market full of people who specialize in recognizing financial disasters will inadvertently share their expertise with the world.

So, in the case of the roulette wheel, we have money committed to the occurrence of an event that cannot be controlled or predicted by the person making the commitment. Moreover, this “investment” is made for no bona fide economic purpose with an expected negative return on investment. In the case of B buying protection through a CDS on a bond he did not own, we have money committed to the occurrence of an event that cannot be controlled by B but can be reasonably predicted by B, and through collective action we have the serendipitous effect of sharing information. To call the latter gambling is to call all of investing gambling. For there is no difference between the latter and buying stock, buying bonds, investing in the college education of your children, etc.

The Credit Default Swap Market Is Not An Insurance Market

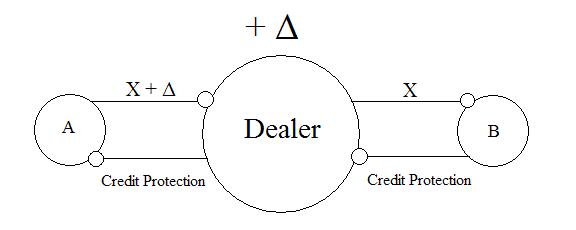

Credit default swaps operate like insurance at a bilateral level. That is, if you only focus on the two parties to a credit default swap, the agreement operates like insurance for both parties. But to do so is to fail to appreciate that a credit default swap is exactly that: a swap, and not insurance. Swap dealers are large players in the swap markets that buy from one party and sell to another, and pocket the difference between the prices at which they buy and sell. In the case of a CDS dealer, dealer (D) sells protection to A and then buys protection from B, and pockets the difference in the spreads between the two transactions. If either A or B has dodgy credit, D will require collateral. Thus, D’s net exposure to the bond is neutral. While this is a simplified explanation, and in reality D’s neutrality will probably be accomplished through a much more complicated set of trades, the end goal of any swap dealer is to get close to neutral and pocket the spread.

That said, insurance companies such as MBIA and AIG did participate in the CDS market, but they did not follow the business model of a swap dealer. Instead, they applied the traditional insurance business model to the credit default swap market, with notoriously less than stellar results. The traditional insurance business model goes like this: issue policies, estimate liabilities on those policies using historical data, pool enough capital to cover those estimated liabilities, and hopefully profit from the returns on the capital pool and the fees charged under the policies. Thus, a traditional insurer is long on the assets it insures while a swap dealer is risk-neutral to the assets on which it is selling protection, so long as its counterparties pay. So, a swap dealer is more concerned about counterparty risk: the risk that one of its counterparties will fail to payout. As mentioned above, if either counterparty appears as if it is unable to pay, it will be required to post collateral. Additionally, as the quality of the assets on which protection is written deteriorates, more collateral will be required. Thus, even in the case of counterparty failure, collateral will mitigate losses.

This collateral feature is missing on both ends of the traditional insurance model. Better put, there is no “other end” for a traditional insurer. That is, the insurance business model does not hedge risk, it absorbs it. So if a traditional insurer sold protection on bonds that had risks it didn’t understand, e.g., mortgage backed securities, and it consequently underestimated the amount of capital it needed to store to meet liabilities, it would be in some serious trouble. A swap dealer in the same situation, even if its counterparties failed to appreciate these same risks, would be compensated gradually over the life of the agreement through collateral.

You will probably disagree with my piece, Rethinking Insurable Interest (http://alephblog.com/2008/10/10/rethinking-insurable-interest/) but I think that like life insurance, there should be insurable interest on the part of those buying default protection. Corporations are legal persons, and they should have a right, the same as natural persons do, to disallow those with no natural insurable interest to seek protection against their death.

The rest is in my article. I’m a life actuary as well as an investor, so that colors my view of the world.

“To call the latter gambling is to call all of investing gambling. For there is no difference between the latter and buying stock, buying bonds, investing in the college education of your children, etc.”

Wow. Another great post. You got right to my question.

Investing involves looking at a business, say, and getting a return for how the business does.When you buy a stock or a bond, you are either purchasing part of the company or loaning it money, but your analysis is based upon and tied to how the business does.

If you bet on sports, say, you have knowledge of the game which you use to determine your wager, but you are betting on an event. You’re not investing in the teams. Now, your knowledge might well lead to predicting which teams are good or bad, but you are still betting on a particular outcome.

CDS’s seem more akin to sports wagering than investment as I’ve just defined them. Both involve money and risk, but they seem to have different qualities and objectives.

I have always thought that investors, as opposed to traders, say, were seen to be different types of creatures. Traders do look more like gamblers than investors.So clearly stocks, bonds, all financial products can involve investment that looks more like gambling.

To the extent that CDS’s were more or less insurance, they seemed to make sense. I’m kind of proud of myself that your post help me get to my question on the same day that article on gambling came out.

http://don-thelibertariandemocrat.blogspot.com/2008/10/it-is-commonly-said-that-derivatives.html

My point was not what the WSJ was saying. I agree that such CDS’s can make sense and even be useful as you describe them, but my fear was that they were being marketed as safe investments, and the risks were not well understood by some of the buyers.

However, until you said this:

“But why should someone profit from ABC’s failure? Because if B’s belief in ABC’s impending failure is shared by others, their collective selfish desire to profit will push the price of protection on ABC’s bonds up, which will signal to the market-at-large that the CDS market believes that there will be an event of default on ABC issued debt. That is, a market full of people who specialize in recognizing financial disasters will inadvertently share their expertise with the world.”

I did not clearly understand the benefits. I had thought that the benefit was hedging your bet or positions by buying a CDS for one direction of movement, and some other form of financial asset for the opposite movement. In other words, it was a way of seeming to minimize risk, but that was really more risky than it seemed.

I hope I have explained my confusion, and thanks again for the explanation. Please don’t post this if it makes no sense. I’m hoping it does, but I’m not sure.

“let’s begin by defining the term “gambling” … ”

The distinction that is usually made by those who use the term “gambling” is between gambling and investment. When savers transfer funds to those with a productive use for those funds we speak of investment. When savers are sold synthetic assets (see for example the WI school board in Monday’s NYT), savers transfer their money to those without a productive use for the money. This is what is meant by gambling — the process of using so-called synthetic assets to divert the funds of savers away from productive investment in the economy. So I don’t think you successfully address the issue of gambling.

Furthermore the fact that swap dealers do not play the role of insurers in the CDS market does not mean that the CDS market is not an insurance market. Swap dealers are not the only participants in the market. Savers (pension funds, municipalities, money funds, etc.) participated in the CDS market via SPEs. Their goal (not that they necessarily understood it) was to sell insurance by “investing” in synthetic assets. Similarly as you note, several insurance companies took only one side of the market. One thing is sure: If there are parties who are net sellers of protection, then there are parties who are net buyers of protection.

Thus you’re not really addressing the question of whether the CDS market is an insurance market — because all you have done is state that certain participants in the market are intermediaries rather than sellers or buyers of insurance. In order to address the insurance question, you need to address the role of CDS for the end users of the product not the intermediaries.

Alas, we must disagree again. CDS are like insurance products in that there is no realisitic means to hedge the exposure. If I sell protection on GS, I have no practical means to hedge that exposure. True, I could short a GS bond, go long a Treasury via repo, etc. But how liquid is the corp bond market? The only practical hedge is to ‘re-insure’ by buying protection from someone else.

Look at the book of any dealer, you will see that they’ve bought protection from their retail customer (corporates, smaller banks), aggregated these positions, and then re-sold the protection to one or more dealers.

Hi ACC,

You said “This is what is meant by gambling — the process of using so-called synthetic assets to divert the funds of savers away from productive investment in the economy.” Derivatives cannot “divert” cash. They are zero sum games. The contracts neither create nor destroy wealth. They merely transfer money that was already in the hands of the contract participants. So, whatever “good use” that money could have been put to can still be achieved. Moreover, even derivatives could divert money away from investment, which they cannot, derivatives facilitate the availability of greater information by creating experts in particular slices of risk, e.g., corporate default.

As for the insurance issue, the statement that “the CDS market is not an insurance” market was made in the context of NY attempting to impose capital requirements on anyone who sells protection to an entity that owns that bond. After reading my article, you cannot possibly believe that this will serve any beneficial purpose for a swap dealer. And I even state that insurers participated in the CDS market. But they didn’t do a very good job. So, I would say that the market, as it exists today, is not an insurance market.

Hi Barry,

Your statement “If I sell protection on GS, I have no practical means to hedge that exposure” is puzzling to me. You can buy protection, which is what you say as well. So how is there “no practical means to hedge?” After buying protection, it is hedged.

Finally, another way for a dealer to hedge is to issue synthetic bonds tied to the CDS protection that dealer sold.

Hi Don,

I’m glad I can help you better understand things. These are complicated issues and it’s not always clear who’s right. One of strange things about a lot of human behavior is that selfish actions can have effects that are beneficial for everyone. I’m not saying this is always the case, but it is quite common. So, look past the greed and ask what is the effect of the greed.

Apologize in advance if I’m beating a dead horse. But the two ‘hedge’ examples that you cited are, to me, just a form of re-insurance.

In any other options market, the seller can hedge by using the underlying, execute spreads (calendar, verticals, straddles, strangles) or outrights at other strikes to hedge his position.

In the CDS, the only real hedge is to buy an offsetting position.

The danger in such a market is akin to having a crowded theatre with but one exit.

You have the same problem with Auction Rate Securities and Tender Option bonds. These are nothing more than put options but the seller of the put option has no means to hedge.

Hi Charles,

“The contracts neither create nor destroy wealth. They merely transfer money that was already in the hands of the contract participants.”

I’m not concerned about wealth being destoyed. I’m worried about CDS being used to divert wealth to the financial industry and away from the real economy. Some of us are not convinced that a financial industry that earns up to 40% of the economy’s income is an efficient allocation of resources.

As for insurance and NYS law: it makes sense to impose capital requirements only on net exposure to each underlying (after adjusting for the default likelihood of each counterparty which the accountants presumably do already). I think this would address your concern about swap dealers being intermediaries rather than insurers.

Hi ACC,

The wealth is not diverted. If it ends up in the hands of financial services, it can still be invested elsewhere.

As for capital requirements, that’s what collateral is for. You don’t need to set aside capital, it comes from the counterparties.

Hi Charles,

I ran into an interesting data point. The US bank subsidiary of Deutsche Bank (FDIC Certificate #623) buys CDS protection but doesn’t sell. In other words, it apparently uses CDS as an insurance product. You can look up this data yourself here. (Look up “Assets and Liabilities”. Under “Memoranda” click on “Derivatives”. The details are all there.)

ACC,

Deutche Bank has more than one subsidiary so the institution as a whole could be and probably is close to CDS neutral. And even if DB did decide to only buy protection, so what? There’s no need for capital reserves because CDS contracts have mark-to-market margin requirements.

I didn’t know where else to write this, but I was wondering if you could do some sort of post in helping people decipher the data that the DTCC just published on their website. Any information is greatly appreciated, and thank you for your previous posts, which really shed light on a topic that has little helpful documentation.

Best Regards

Pingback: A little light shed on credit default swap market | Zensible

Pingback: A little light shed on credit default swap market | The Stock Watch

How much capital does it take to affect pricing in the CDS market vs. the regular bond market?

The issue I see is that the CDS pricing creates a signal, which other markets trade on. If you buy $100 million of protection vs. default for a medium sized financial for not so much capital, don’t you have the ability to create a self-fulfilling “run on the bank” for not a lot of capital outlay?

If the product can effectively be used to swing market sentiment on a company, do you view that as a legitimate form of hedging?

Pingback: USBusinessEdition » Blog Archive » A little light shed on credit default swap market

I wonder whether you could take readers through the recent settlement of Lehman CDS. It seems to me that the 90% cash-settled loss reported in the papers was far larger than a seller of CDS protection would have budgeted for: consider that an investment bank is levered 30:1; then the bank goes bust and it turns out to have lost five times its capital. So that would still leave 26/30 for bond holders. OK some creditors will be senior or hold collateral, but still the bank should cease trading long before debt recovery is down to 10%.

If in the end Lehman bonds are worth 45% will there be a retrospective adjustement of cash-setled CDS or are sellers of insurance dependent on a pessimistic estimate of recovery value? To insure an expectation is hard to justify as a business plan.

Hi RichL,

What you are saying is that the CDS market is now a “price discovery” market. That is, the market looks to the CDS market for prices and therefore indications of credit quality.

As a theoretical matter, yes, you could bid up the price of protection. However, in an environment where people are highly concerned about default, e.g., in the current market, it would not be cheap to do so. Protection on some companies has reached 50,000 bp, or 50%. So, your 100 mil purchase of protection would cost you 50 mil per year. Not so cheap.

Hi PRalli,

I’d rather not go through the process of an ISDA auction. It’s rather boring, highly technical and frankly not that important. (My apologies to the fine people who design and run these auctions, but it’s just a little too much for my blog).

As for banks not budgeting enough, if you read the above article again, you’ll note that the swap dealers (which as far as I know are all banks) are neutral on their trading books (I have heard that the dealer institutions as a whole are net buyers of protection, but don’t quote me on that). As such, they don’t need to allocate any capital to CDS payouts, they just have to ensure payment from their counterparties.

Pingback: A little light shed on credit default swap market | the daily john

Pingback: You’re Trespassing On My Credit Event « Derivative Dribble

Pingback: A little light shed on credit default swap market | Investing Master

Pingback: Why Credit Default Swaps? « Derivative Dribble

Pingback: Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Soros! « Derivative Dribble

Now I see why we are in such a perdicament. It is becuase scumbags like all of you people posting here, who have no moral compass to see that the issue is wrapped up in your terminoloy.

“Buying protection” “Gambling” of course these credit default swap pieces of shit were like ridiculously large balloons that you fucking scumbags on Wallstreet have blown up over the last 8 years since the regulations changed. It is simple to see your obsfiscation of the issue, in your confusing bafflegab. Making it simple shows that:

Yes, it was gambling,

Yes, it is illegal

Yes, it is more like 160 TRILLION outstanding in CDS

Yes, the Wall street scumsucking greedy assed bastards have ruined the economy, and they will hang for it. The revolution will happen right in Manhattan, so you better have your plane tickets handy at all times. It will only take a simple little thing to set people off, a bank failure, maybe Citibank, and voila, 100,000 or 200,000 people come pouring out of the buildings surrounding Wall st. to get some revenge. Mark my words assholes, your time has come.

Do you even read anything?

Click to access 200747pap.pdf

As of Dec 2006, Total outstanding CDS (adjusted for double counting) was 28.838 TRILLION. You should get out more and not stay in the basement counting your money Mr. Burns.

I have no expectation that you will allow this post, but that just proves what a complete sham you are.

“Yes, it was gambling”

Again, if utilizing CDS to hedge and trade credit risk is gambling, then so is investing in futures, stocks, bonds, and the like.

“Yes, it is illegal.” That is categorically false. The Commidity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 specifically mentions CDS.

“Yes, it is more like 160 TRILLION outstanding in CDS.” First, your notional amount is incorrect. Second, the figure you intended to report (and did in your follow up post) is the gross notional amount of the contracts, before netting, and is not an indicator of the amount of capital actually at play.

“Yes, the Wall street scumsucking greedy assed bastards have ruined the economy, and they will hang for it.” First, you have produce no evidence supporting your statement. Second, in our system of justice, we do not impose the death penalty for economic crimes.

“As of Dec 2006, Total outstanding CDS (adjusted for double counting) was 28.838 TRILLION.”

Even if you adjust for double counting, the total notional amount is not an accurate indicator because it is not a net figure.

“I have no expectation that you will allow this post, but that just proves what a complete sham you are.”

You’ll note that I have made no representations about myself. And you’ll also note that I am open to criticism.

That said, I put a lot of thought and effort into my articles. I expect the same in return in the comments. Your comments are idiotic, uninformed, and vulgar.

As for your wish for a revolution, if such an event occurs, you will most certainly regret ever wishing for it. People with wits as dim as yours do not fair well in a world without law and order.

Pingback: Credit Default Swap « Processing Knowledge

your discussion of swap mechanics is interesting but ignores the problem of accounting legerdemain. We now have trillions in off balance sheet obligations affecting the credit worthiness of our public corporations. How is one to know which company stands to be blown up by a ‘rare event’, perhaps because a counterparty turned out to be a financial black hole?